Introduction

I started playing Dota at some point during the end of July 2014. At the time I was looking for a new match-based game to play since my interest in Team Fortress 2 was waning. Several of my close friends were actively playing Dota at the time, so there was a social draw to play as well. I clocked several hundred hours during the Fall 2014 school term, but didn’t really start taking the game seriously until the following year. Aside from commitments like internships and school work, I ended up spending most of of my spare time playing, watching or reading about Dota.

One of the things I’ve always been proud of is the amount of time I spend writing code for its own sake. The majority of my development experience, especially in the field of computer graphics, comes from personal projects and research. Playing Dota as a sort of “full time hobby” didn’t leave room for anything else; as such, I more or less stopped working on the side projects altogether. Eventually this caught up with me and I started to question whether or not continuing to play was worthwhile.

My last match of Dota was in early October, before taking a trip home to visit my parents. Originally my break from playing was supposed to last for a week, however I ended up reflecting on the past year and chose to stop playing indefinitely. The game was always enjoyable for me — I didn’t quit because of boredom or frustration, but because it seemed that my time was better spent on other things.

It’s taken me a while to write this post since there was some website maintenance that needed to be completed first. I figured Dota was a suitable topic for my first post in a year, since it was one of the primary reasons I stopped updating my website in the first place. The next section provides an introduction to the game itself, while the rest of this post is a reflection on my experience playing the game.

Dota 2

Defense of the Ancients (DotA) started life as a Warcraft III mod. The original game was clunky and limited by the tools in the Warcraft editor, but it developed a significant userbase. Eventually the maintainer of DotA was offered a position at the game company Valve. DotA was rewritten from scratch using Valve’s Source Engine and released/rebranded for free as Dota 2 in 2013.

Dota 2 has since become one of Valve’s most successful games. It has a huge competitive following which is popular all over the world, unlike Starcraft. Valve sponsors a major tournament each year called The International; the 2015 event had a total prize pool of 18 million dollars, most of which was crowdfunded by the community.

It’s quite challenging to summarize the game mechanics in a single blog post as Dota 2 is extremely complex. In short, the game is a 5 vs. 5 match where both teams try to destroy their opponents’ ancient. Ancients are located at opposite corners of a square map, behind three layers of towers and various other defensive buildings. Each team will try to make use of the resources available on the map, slowly chipping away at their opponents’ structures and gaining map control. Dota is a real time game, so players are constantly clicking/pressing keys to move and perform actions in the game. Reaction time and quick decision making come into play in a lot of situations.

The Dota 2 map, showing the two teams buildings

At the beginning of a match, each of the 10 players selects a hero from a a pool of 122 choices (duplicate picks are not allowed). This means that the number of hero combinations that can occur in any given match is on the order of 1020. Each hero has between four to six abilities which become stronger throughout the duration of the match. Not all heroes synergize well with each other, of course, and some heroes are strong counters to others. On top of this each player can equip up to six items on their hero at a time. Hundreds of different items are available, each of which is useful in specific situations and pointless in others.

Needless to say, communication and teamwork are crucial to victory in a game of Dota. For example, most heroes with a disable — a type of ability that can temporarily immobilize an enemy hero — aren’t able to deal large amounts of damage on their own. On the other hand, heroes with high damage output often lack a way to hold their target in place or keep up with them. Picking a combination of disabling and damage-dealing heroes is a step in the right direction, but the players also need to be coordinated to maximize effectiveness. Different disables have different durations, and players can buy items that make them immune to the effects of some (but not all) abilities. This example only covers a small subset of the full set of game mechanics — each ability in the game is unique, with effects including healing, single-target damage, area damage, etc.

A fight involving many heroes. numerous abilities and items are being used here

A single player can use the Dota matchmaking system to find a game with other random players of around the same skill level. Alternatively, groups of between two to five players can form a group and queue for a match together. This will guarantee that the group of players is on the same team. Colloquially, this is referred to as an n stack, where n is the number of people in the group, e.g. a three stack. Playing in a stack has numerous benefits, the most significant is that generally everyone knows each other. Usually stacks are on some sort of voice call like Skype as well, which helps with in-game communication.

The Time Commitment

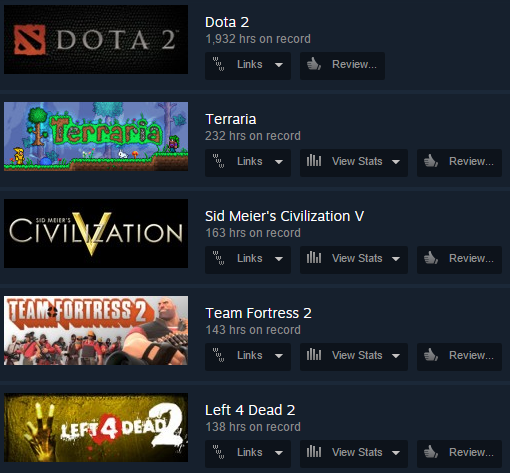

According to Steam, I’ve had the Dota 2 game client running for just shy of 2,000 hours. My match stats indicate that I played around 1,200 games, which probably amounts to about 1,500 hours of actual gameplay time. The remaining hours come from practicing against AI, watching professional players and leaving the game idle while eating, cooking, etc. For comparison, I’ve only spent around 200 hours on Terraria, my second most played game

One of the problems that Dota caused for me was that, to some extent, player skill level is correlated with the amount of time spent playing. The complex mechanics and sheer volume of information takes hundreds of hours to absorb. On top of that, every few months a new major patch is released that tweaks various game mechanics and sometimes adds new heroes or items to the game. The patch usually results in slight changes in the way the game is played — some heroes become stronger while others become weaker, new team compositions are discovered, etc. Amongst the Dota community this is referred to as the meta game, or simply the meta.

While it’s certainly possible to play less frequently, perhaps one or two games a week, the nature of Dota makes it hard for casual players to really excel at the game. Much like a sport, regular practice is needed to maintain even a constant level of performance. Since I enjoyed winning games of Dota, it made sense to commit the time needed to keep up with the meta and be good at the game in general. This is not entirely the fault of the game of course, but in part caused by the personality of the ex Dota player in question.

Social Aspects of Dota

As with any multiplayer online game, Dota puts players in contact with people from around the world. Often times random teammates aren’t exactly the most amicable human beings, however I ended up becoming good friends with several people I met in-game. Initially I played Dota as part of a three stack, along with my roommate and another friend from school. In one of our games we had a friendly teammate, Peter, and ended up adding him to our stack for the rest of the evening. We got along well and Peter was about the same skill level as us, so we ended up playing as a four stack on a regular basis. He introduced us to his friends that played Dota, further expanding the number of people I knew that played the game.

Out of all the matches of Dota I played, the most enjoyable were with a group of people I met through Peter. We typically played as five in a competitive game mode called Captains Mode. Rather than players picking heroes on their own, each team chooses a captain, who then drafts a line up of heroes for the team to play. The games were more serious, but in many ways this also made them more fun.

I think the social aspect of playing the game was one of the primary reasons I continued to play. I still keep in touch with a few of the friends I made through Dota, through a combination of Facebook and Steam messages.

Mental Exercise from Dota

On a more personal level, Dota fulfilled my need for a regular challenge with a concrete measure of progress. Prior to playing Dota I used to play a lot of online chess, both against other people and AI. I didn’t put anywhere close to as much time into chess, but I did spend evenings reading up on opening theory and looking at famous games. In many ways Dota and chess are quite similar in that they both have complex theory and take many years to master. Dota of course has team elements that are completely lacking in chess and chess is turn based.

Now that I no longer play Dota, I’ve actually started to play online chess again, as well as the occasional game of Gomoku with my roommate. I think the reason for this is that when taking breaks from coding I prefer to do something active instead of passive. A video game or strategy board game requires the player to take an active role; when watching a movie or TV show the viewer can zone out completely. That’s not to say I don’t enjoy watching a good TV show — I just save it for when I don’t have the energy to do anything else.

Game Mechanics

From a game design standpoint, Dota is something of a mystery as it breaks a lot of rules. Conventional wisdom suggests that a well designed game should be accessible to new players. Modern games don’t come with manuals — players are usually able to figure out how the game works simply by playing it. Sometimes this involves a tutorial mode that introduces the core mechanics, but the learning almost always happens in the game itself. Dota is so complex that serious players often spend time reading guides or looking up information in the Dota Wiki.

One of the main reasons is that many aspects of Dota aren’t always internally consistent or obvious. For example, an item called a force staff allows the player to move themselves a certain distance in a short amount of time, instead of walking. A blink dagger is an item with a similar purpose, however the range is slightly larger and the travel time is instant. A force staff can be used to move a teammate around, while a blink dagger can only be used by the owner of the item. A blink dagger cannot be used if the owner has taken damage within a certain period of time, however this damage restriction doesn’t apply to a force staff. A blink dagger and a fast reaction time can be used to dodge some types of incoming projectiles (but not all of them!), while a force staff in general can’t. Additionally, if a user clicks too far with their blink dagger, rather than moving the maximum distance the player will move a reduced distance as penalty for “over using” the blink dagger.

In-game icons for a force staff and a blink dagger

Although both items are considered to be “mobility items” that help a player move around faster, the subtle differences are extremely important. A lot of the essential information on items and abilities is difficult to look up in-game. New players usually end up discovering the information by reading information outside of the game or by being flamed by their teammates.

In some ways I suppose Dota is similar to EVE Online and Dwarf Fortress in that regard, as both of those games are renowned for their complexity. However, Dota has a much larger player base with millions of active users and still experiencing user growth. In the last few patches I played, it was clear that the developers were in the motions of making some of the mechanics more consistent and easier to understand. I suspect the game will always have quite a steep and intimidating learning curve though; in some ways it is a feature rather than a drawback.

Closing Thoughts

As I mentioned earlier I don’t regret sinking 2K hours into playing and watching Dota matches. I still follow my favorite professional players and teams, particularly around the time of major tournaments, and watch their matches on Twitch. Likewise, I’m still in touch with some of the new acquaintances I made while playing. For someone interested in game development such as myself, Dota is a also a great resource for examples of both good and bad game design. That said, it’s unlikely that I’ll spend the same amount of time on another video game in the future.